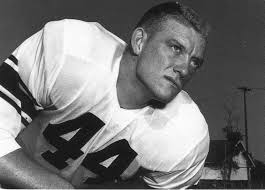

John David Crow died Wednesday. Until Johnny Football, he was the only football player from Texas A&M University to win the Heisman Trophy. He played under the legendary Paul ‘Bear’ Bryant at A&M and for all of Bryant’s success, Crow was the his only player to win the award given annually to the nation’s best collegiate football player. Crow had a productive professional football career making the Pro-Bowl four times. He was also the Athletic Director at A&M from 1989 to 1993. So here’s to John David Crow, one of the Junction Boys and one of the greatest players in the history of Texas A&M. Finally, let me say something I almost never say, Gig ‘Em, John David.

John David Crow died Wednesday. Until Johnny Football, he was the only football player from Texas A&M University to win the Heisman Trophy. He played under the legendary Paul ‘Bear’ Bryant at A&M and for all of Bryant’s success, Crow was the his only player to win the award given annually to the nation’s best collegiate football player. Crow had a productive professional football career making the Pro-Bowl four times. He was also the Athletic Director at A&M from 1989 to 1993. So here’s to John David Crow, one of the Junction Boys and one of the greatest players in the history of Texas A&M. Finally, let me say something I almost never say, Gig ‘Em, John David.

I thought about John David Crow and his legacy of greatness when I read an article in the June issue of the Harvard Business Review (HBR), entitled “You Need an Innovation Strategy”, by Gary P. Pisano. While Pisano’s article dealt more generally with innovation in marketing, I found it highly relevant for the Chief Compliance Officer (CCO) or compliance practitioner, particularly in the context a Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) compliance program. Earlier this week, the Department of Justice (DOJ) announced the resolution of a FCPA investigation involving IAP Worldwide Services, Inc. (IAP) via a Non-Prosecution Agreement (NPA). In the NPA, the company committed to implementing and enhancing a best practices FCPA compliance program. Listed at element 18 of its compliance program is the following: “The Company will conduct periodic reviews and testing of its anti-corruption compliance code, policies, and procedures designed to evaluate and improve their effectiveness in preventing and detecting violations of anti-corruption laws and the Company’s anti-corruption code, policies, and procedures, taking into account relevant developments in the field and evolving international and industry standards.”[Emphasis supplied]

This means that the DOJ expects innovation in your compliance program to keep up with evolving international and industry standards. This requires you to implement an innovation strategy. While Pisano’s article does not specifically focus on compliance, I found that its concepts would help a CCO or compliance practitioner sustain the mandate for innovation in a compliance regime. Pisano’s article begins by stating the problem that many companies face is that “innovation remains a frustrating pursuit.” While acknowledging that failure to execute is an issue, Pisano believes the issue is deeper than simply a failure to execute, he believes there is a “lack of an innovation strategy.”

I found some of his basic definitions most useful for the compliance practitioner to think through innovation in the compliance function. Pisano wrote, “A strategy is nothing more than a commitment to a set of coherent, mutually reinforcing policies or behaviors aimed at achieving a specific competitive goal. Good strategies promote alignment among diverse groups within an organization, clarify objectives and priorities, and help focus efforts around them. Companies regularly define their overall business strategy (their scope and positioning) and specify how various functions – such as marketing, operations, finance, and R&D – will support it. But during my more than two decades studying and consulting for companies in a broad range of industries, I have found that firms rarely articulate strategies to align their innovation efforts with their business strategies.”

The key to success is something that every CCO or compliance practitioner should take to heart. Paraphrasing Pisano for the compliance practitioner is that the compliance function “should articulate an innovation strategy that stipulates how their [compliance] innovation efforts will support the overall business strategy.” Moreover, “creating an innovation strategy involves determining how innovation will create value for customers [of compliance, i.e. Employees], how the company will capture that [compliance] value, and which types of [compliance] innovation to pursue.”

Pisano posed several questions around this key area of connecting innovation to strategy. Initially he asked, “How will innovation create value for potential customers?” In my formula, customers become employees or others who will make use of your compliance innovation going forward. Here you should focus on the benefit for your end-using customer. Your innovation can make compliance faster, easier, quicker, more nimble and so on. But focus on that creation of value going forward. Pisano’s next question was “How will the company capture a shore of the value its innovations generate?” He suggests companies think through how to “keep their own position in the [compliance] ecosystem strong” through innovation. Pisano next asked, “What types of innovation will allow the company to create and capture value, and what resources should each type receive?” Here Pisano notes two major forms of innovation equally applicable to the CCO or compliance practitioner. They are a change in technology and a change in a business process. Both are equally valid.

Another problem that Pisano addresses is termed “overcoming prevailing winds” and this means that innovation can be driven downward or backward if there is not sufficient management support. This means not only must there be sufficient resource allocations but management must also incentivize the business units to proceed with implementing the innovations, particularly “when an organization needs to change its prevailing patterns.”

Another area Pisano addresses is “managing trade-offs” because it is inherent in any innovation strategy that there will be trade-offs. Here he terms the two key differences as “supply-push” and “demand-pull”. The supply-push approach comes when your innovation is focused on something that does not yet exist, for example if you are initially implementing a FCPA compliance regime. The demand-pull approach works more closely with your existing customer base to determine what they might need and work to implement innovation around those needs.

Interestingly Pisano ends his article with a discussion about “the leadership challenge”. I say interestingly because I would have thought that was required up front as it is the function of senior management to create the capacity for innovation in the first instance. Pisano writes, “There are four essential tasks in creating and implementing an innovation strategy.” Task 1 is to “answer the question “How are we expecting innovation to create value for customers and for our company?” and then explain that to the organization.” Task 2 “is to create a high-level plan for allocating resources to the different kinds of innovation.” Task 3 is “to manage trade-offs. Because every function will naturally want to serve its own interests, only senior leaders can make the choices that are best for the whole company.” Finally, task 4 dovetails with what almost every DOJ/SEC speaker I have ever heard say when they talk about the basics of any best practices compliance program. It is that “innovation strategies must evolve. Any strategy represents a hypothesis that is tested against the unfolding realities of markets, technologies, regulations, and competitors. Just as product designs must evolve to stay competitive, so too must innovation strategies. Like the process of innovation itself, an innovation strategy involves continual experimentation, learning, and adaptation.”

Pisano’s article provides the CCO or compliance practitioner with a framework to think through to help bring the innovation to a compliance program. I would have put leadership first, both in the compliance department and at senior management level. But however you go about it, you must recognize that your compliance program will have to evolve. That is one of the key differences between those who advocate static compliance standards embodied in a written compliance program and those who advocate that it is Doing Compliance that creates an active, vibrant and effect compliance program.

This publication contains general information only and is based on the experiences and research of the author. The author is not, by means of this publication, rendering business, legal advice, or other professional advice or services. This publication is not a substitute for such legal advice or services, nor should it be used as a basis for any decision or action that may affect your business. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your business, you should consult a qualified legal advisor. The author, his affiliates, and related entities shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person or entity that relies on this publication. The Author gives his permission to link, post, distribute, or reference this article for any lawful purpose, provided attribution is made to the author. The author can be reached at tfox@tfoxlaw.com.

© Thomas R. Fox, 2015